9 March 2026

TeXmacs plugins

I like TeXmacs. There are several difficulties when I use it,

but still, I like the concept: To have one big system that ensures high-quality typesetting.

The output is like LaTeX's output, but TeXmacs tries to avoid supporting thousands of extra packages

and the difficulty of interferences when some packages are incompatible.

What I really like is sessions. Users can put the inputs and outputs of conversations

during computer algebra computations into TeXmacs documents, save them, and when reopening

the document, sessions can be edited or continued. Of course, there are several limitations,

but the basic concept is working well. Scientific results can be reproduced in a simple way.

I decided to write a plugin for GeoGebra Discovery's

release page, version 2026Feb18. The results are promising, there are, however, some issues to fix

in future releases, including full muting of Giac's

and Tarski's error messages, and further muting

of GeoGebra on demand.

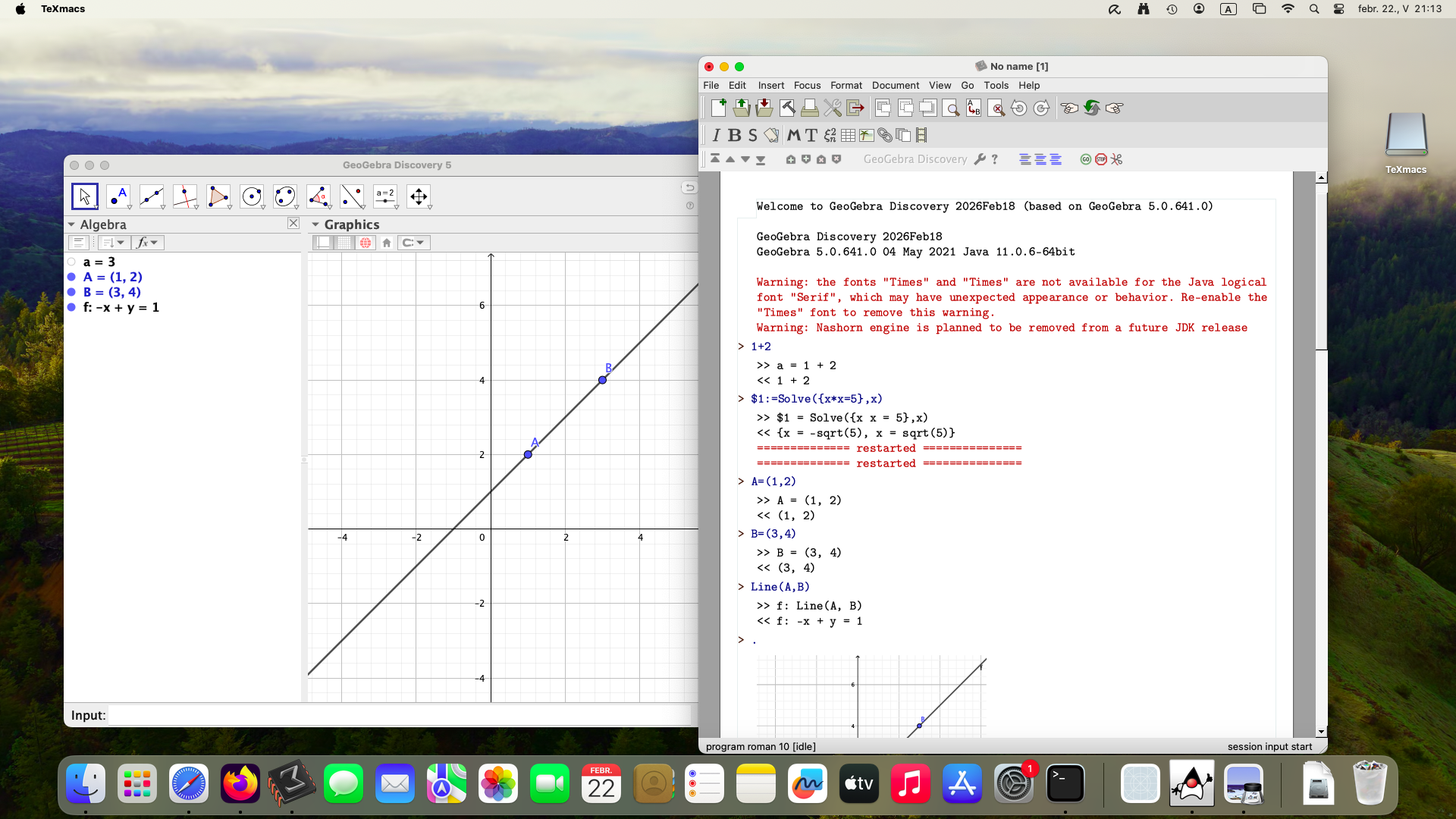

In this figure the macOS version of TeXmacs is shown, after starting a GeoGebra Discovery session.

The user is typing various commands, including one that is to be sent to the CAS View and to be computed symbolically.

The red messages come from the standard error and could be removed by hand, but for the long term,

it would be more elegant to not show them at all. All inputs are supported by GeoGebra automagically,

except the input . which creates an immediate screenshot of the Graphics View and the picture will

be inserted in the TeXmacs document as PostScript.

While there are some feature requests on my own side, the first public version is surprisingly nice.

It is already mature enough to start writing a book with reproducible GeoGebra constructions in mind.

The GeoGebra language seems rich enough to avoid using the toolbar, to drag and drop objects,

to enable or disable them, to start an animation or stop it, among many other features.

Another plugin

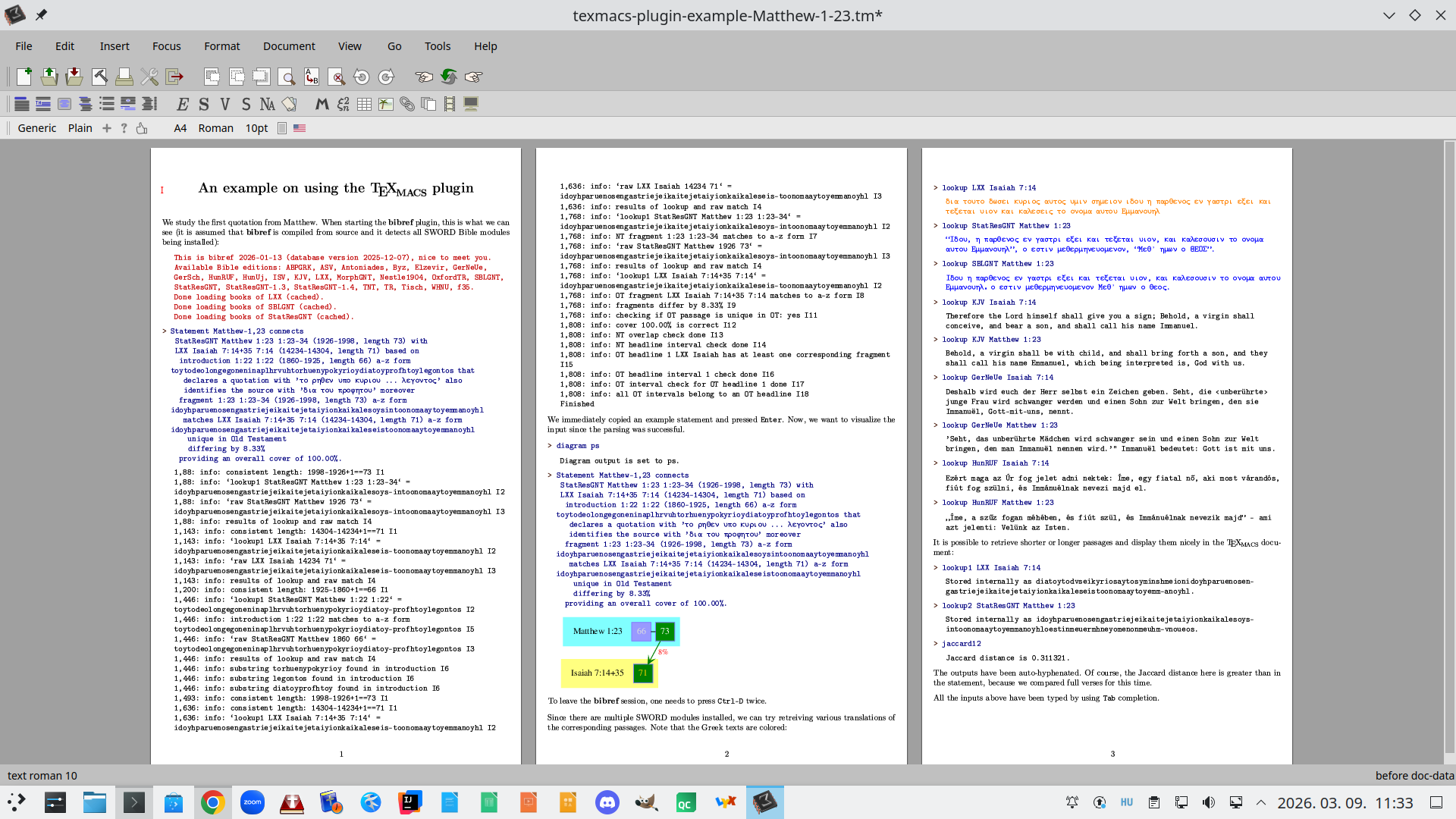

Meanwhile a have second book in mind to write: on reproducible research concerning old historical

texts, in particular, studying ancient versions of the Bible. My research project called bibref

already reached a mature stage, but recording of the scientific results was still a question.

Should I use LaTeX and copy-paste data from the application in the LaTeX document, or use something

more handy? Here I decided to play with TeXmacs again, and I have a nice result which could be

a good solution.

The bibref tool has a command line version, so the first steps when programming a new plugin

were easier as for GeoGebra Discovery.

In this second project I tried to be more pragmatical by focusing on tab completion as well.

To be honest, it was extremely difficult to find the right way how the communication protocol should

work between bibref and TeXmacs. Maybe I missed the correct and most relevant documentation,

and by spending hours of conversations with an AI bot I had to conclude that at the end of the day,

I am still almost alone.

Luckily, the tab completion works very efficiently now, however, I would like to see some syntax

highlighting in the input code as well. Until now I did not find a solution how to do that.

Here you can find two TeXmacs files and the installation notes of the new plugin.

They show the current state of my work.

Writing the plugin for bibref was technically more challenging, because I had to extend the

command line version of bibref to support automatic conversion of GraphViz files to PostScript.

Luckily, the graphviz library has a good support to do that, not only for PostScript but also for SVG.

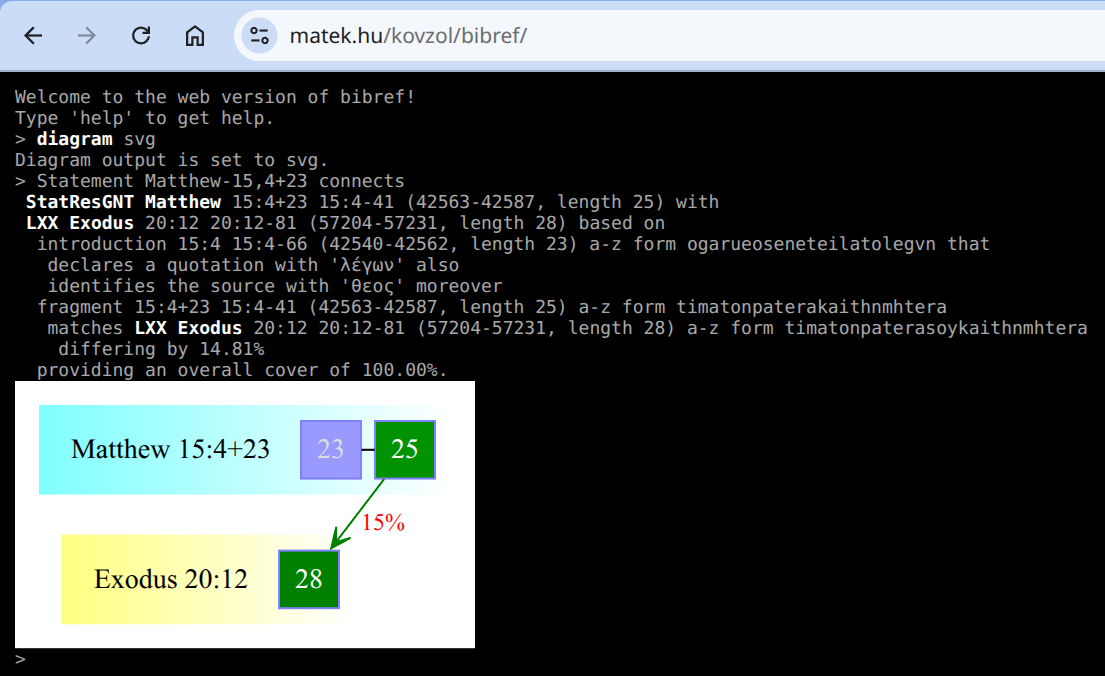

As an extra result, the web variant of the command line version of bibref can display the

SVG output directly in the terminal window:

Such a terminal session cannot be saved (at the moment), so TeXmacs is definitely better if

reproducible data is prioritized.

Continue reading…

- 15 January 2026—Towards reproducible builds via Docker

- 24 December 2025—Statement diagrams based on LXX 3.2

- 23 December 2025—bibref: Support for LXX 3.2 and StatResGNT 1.4, and some technical infos

- 30 October 2025—GeoGebra Discovery reaches 2000 installations via Snapcraft

- 23 August 2025—bibref: German language support

- 14 August 2025—Module LXX can be upgraded from 3.0 to 3.2 just with little pain

- 13 August 2025—GraphViz as a WebAssembly module

- 10 July 2025—Connecting ISBTF's LXX-NT database with bibref

- 5 July 2025—JGEX via CheerpJ

- 20 April 2025—An online Qt GUI version of bibref

- 29 March 2025—An allusion on Palm Sunday

- 8 March 2025—Statement analysis in bibref

- 7 March 2025—Developing C++ code for desktop and web with cmake

- 7 February 2025—Update to LXX 3.0: Part 2

- 5 February 2025—Deuterocanonical books in the bibref project

- 23 January 2025—Statements connecting LXX and StatResGNT

- 6 January 2025—Treasure of Count Goldenwald

- 2 January 2025—Statements on Bible references: Part 2

- 22 August 2024—Compiling and running bibref-qt on Wine

- 5 August 2024—Statements on Bible references

- 30 July 2024—Difficulty of geometry statements

- 11 March 2024—Qt version of bibref

- 2 January 2024—xaos.app

- 10 December 2023—JGEX 0.81 (in Hungarian)

- 11 November 2023—Debut of GNU Aris in WebAssembly

- 30 August 2023—XaoS in WebAssembly

- 31 July 2023—Statistical Restoration Greek New Testament

- 16 April 2023—Tube amoeba

- 15 April 2023—Torus puzzle

- 19 September 2022—Stephen's defense speech

- 25 August 2022—A general visualization

- 23 August 2022—Long false positives

- 31 July 2022—Isaiah, a second summary

- 25 July 2022—Matthew, a summary

- 17 July 2022—On the Wuppertal Project, concerning Matthew

- 28 June 2022—Terminals on the web

- 7 April 2022—A summary

- 2 April 2022—Compiling Giac via MSYS2/CLANG32

- 30 March 2022—Isaiah: Part 7

- 23 March 2022—Isaiah: Part 6

- 15 March 2022—Isaiah: Part 5

- 7 March 2022—Isaiah: Part 4

- 2 March 2022—Isaiah: Part 3

- 26 February 2022—Isaiah: Part 2

- 19 February 2022—Isaiah: Part 1

- 15 February 2022—A classification of structure diagrams

- 12 February 2022—Supporting logic with technology: Part 2

- 7 February 2022—The Psalms: Part 2

- 6 February 2022—The Psalms

- 5 February 2022—A summary on the Romans

- 3 February 2022—Non-literal matches in the Romans: Part 2

- 2 February 2022—Non-literal matches: Jaccard distance

- 1 February 2022—Literal matches: the minunique and getrefs algorithms

- 31 January 2022—Literal matches: minimal uniquity and maximal extension

- 26 January 2022—Non-literal matches in the Romans

- 24 January 2022—Developing Giac with Qt Creator on Windows

- 23 January 2022—A student of Gamaliel's

- 20 January 2022—Reproducibility and imperfection

- 17 January 2022—Order in chaos

- 12 January 2022—Web version of bibref

- 2 November 2021—Supporting logic in function calculus

- 28 October 2021—Proving inequalities

- 27 October 2021—Discovering geometric inequalities

- 1 October 2021—Web version of Tarski

- 9 July 2021—Embedding realgeom in GeoGebra

- 26 January 2021—ApplyMap

- 25 January 2021—Comparison improvements

- 29 December 2020—Pete-Dőtsch theorem

- 18 November 2020—Ellipsograph of Archimedes as a simple LEGO construction

- 17 November 2020—Offsets of a trifolium

- 11 November 2020—Explore envelopes easily!

- 31 October 2020—Points attached to an algebraic curve…

- 19 October 2020—Detection of perpendicular lines…

- 6 October 2020—Better language support…

- 29 September 2020—A new GeoGebra version with better angle bisectors…

- 28 September 2020—I restart my blog…

|

Zoltán Kovács Linz School of Education Johannes Kepler University Altenberger Strasse 69 A-4040 Linz |