17 January 2022

Order in chaos

But the path of the just is as the shining light,

that shineth more and more unto the perfect day.

— King Solomon (Proverbs 4:18)

that shineth more and more unto the perfect day.

— King Solomon (Proverbs 4:18)

Have you ever started reading the number one bestseller of the world?

I mean here the Bible, which, according to several sources (see

this, for example)

has been sold in more than 5 billion copies in the world.

And did you find

some order in that book?

Some parts of it – for example, the Gospels –

are quite simple to read: they communicate a very clear message,

but at the same time they deliver a deep knowledge.

The Bible is a collection of several books. The first part, the Old Testament, is

a canonical collection of Hebrew scriptures, but the second part (the New Testament) was

written by Christians, followers of Jesus.

Christians claim that Jesus was the promised Messiah sent by God.

In fact, a great part of the New Testament seem to prove this doctrine, by

using many ways: mostly by telling stories about Jesus from his supernatural birth through his life

until his death (and his resurrection!), and the supernatural deeds of his mortal followers.

An important method of verificating Jesus' identity is to quote texts from the Old Testament and explain that they have

a direct connection with the happenings in the New Testament including doctrinal questions too.

All this means that quotations play an important role in the New Testament. The Jewish culture

and theology also rely on quoting the Old Testament and explaining it. As a result, the text of the Old Testament

is handled very carefully by Christians and Jews. At the end of the day, it is considered as God's revelation,

and therefore perfect and complete.

In the following blog entries, I am going to demonstrate how the connection between the Old and New Testament can be

explained by quotations appearing in the New Testament, by using mechanical tools. I consider it

important to use mechanical methods to avoid personal preconceptions as much as possible.

In fact, comparison of two texts is much simpler if they are in the same language. In our case,

the Old Testament is written in Hebrew, but the New Testament was written in Greek. The oldest manuscript

of the Hebrew Old Testament is the Leningrad Codex, dated back to 1008 CE.

For the New Testament, the oldest manuscripts are the Codex Vaticanus

and the Codex Sinaiticus, both of them can be traced back to the 4th century.

Both of these old manuscripts contain a Greek translation of the Old Testament; however, some parts of

the texts are lost. Being familiar with later manuscripts we can have a guess how the original texts looked like.

The translation process from Hebrew into Greek began in the 3rd and finished in the 2nd

century BCE. It was initiated by King Ptolemy the Great, and the result was

called Septuagint. In the ancient world, more

than a hundred years before the arrival of Jesus, it was already possible to read the Old Testament

in lingua franca, the common language:

Greek. In the New Testament we also read about a kind

of internationalization process of the Jewish theology, by moving the focus from the Jews to other nations.

We use a digital tool embedded in this web page that is able to compare Greek texts:

the Greek translation of the Hebrew original of the Old Testament to the Greek text of the New Testament.

Some readers who have roots in the Jewish tradition may disagree and say that this is not a good idea:

the original Hebrew text should be read in Hebrew, right? There are actually some slight differences

between the original text and the translation. Also, some parts cannot even be translated perfectly

(see, for example, Psalm 119 which is an

acrostic poem). But, in fact, there are important arguments for using

the Greek translation of the Hebrew text in a research project:

- The Greek translation was widely used in the ancient times, even in the New Testament there is ample evidence of this.

- Important people who had Jewish roots like the Apostle Paul preferred using the Greek text in many situations instead of the original Hebrew.

- The internationalization process is mentioned several times in the New Testament, predicting the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

Let us have a look at the digital tool this web page provides! There is a command line interface to

bibref below that allows the user to use a digitalized

version of the Septuagint (called LXX), and the Greek New Testament (called SBLGNT).

Our research question is the following: Did the authors of the New Testament quote

the texts from the Old Testament accurately? This is a very substantial fundamental question if we want to take the Bible

seriously. I would like to answer this question unbiased, by using mechanical methods as much as possible.

To get a first impression I have already prepared a command line for you: just click in the pink input box and press ENTER to have a try.

First, we will get a verse of the English Bible (KJV),

from the Book of Isaiah, to approach the topic a bit. This is, of course, written in English,

so we may want to see the Greek text instead, to get a closer look.

Please try the command lookup LXX Isaiah 7:14

either by editing the input by hand and pressing ENTER again, or by using copy-paste. Do not worry if you don't speak Greek:

we will be working with the texts just mechanically.

Let us try to fetch a quotation of this verse from the New Testament:

please type (or copy-paste) lookup SBLGNT Matthew 1:23.

You can confirm that some matches should indeed appear in the two texts. By issuing

lookup KJV Matthew 1:23 you can read the English

translation as well.

Now we will compare these two Greek texts. The English translation suggests that we may want to skip

the introductory part of Isaiah and the ending part of Matthew. We can store the relevant part of Isaiah by using

the command

text1 ιδου η παρθενος εν γαστρι εξει και τεξεται υιον και καλεσεις το ονομα αυτου εμμανουηλ.

This will put the text on clipboard 1.

On the other hand, to store the second text on clipboard 2 you need to type

text2 Ιδου η παρθενος εν γαστρι εξει και τεξεται υιον, και καλεσουσιν το ονομα αυτου Εμμανουηλ.

To compare them mechanically you have two options. You can either use the Jaccard

distance for the two texts by

issuing the command jaccard12 or use an optional comparison with the command compare12.

Both will give

you a number near 0.08 – this simply means that these two texts substantially match, since they differ in 8%.

More on mechanization

Of course, one needs to know these two relevant parts of the Bible in advance, to verify the

assumption that these texts match. If one knows only the first text from LXX, there is already a tool

that helps find the matching part from SBLGNT. This is how it works: one needs to type

getrefs SBLGNT LXX Isaiah 7:14.

By pressing ENTER, your browser may process for a couple of seconds – here the whole Bible must be checked,

so be patient.

The result is somewhat more complicated. The program gives line by line which texts from the New

Testament have a partial but literal match with the text from Isaiah. Some lines may be just accidental,

but the last ones are often correct matches. Here we mention two of them:

- LXX Isaiah 7:14+85 7:14 = SBLGNT Matthew 1:23+52 1:23-34 (length=21, pos1=14284, pos2=1974)

- LXX Isaiah 7:14+35 7:14-24 = SBLGNT Matthew 1:23 1:23-60 (length=47, pos1=14234, pos2=1922)

Another option to perform a mechanical check is to put the two long texts in the clipboards by

explicitly defining their starts and ends. This is how it works:

lookup1 LXX Isaiah 7:14+35 7:14 and

lookup2 SBLGNT Matthew 1:23 1:23-34.

Finally, the command

jaccard12 will compute the Jaccard distance

for the two texts in the clipboards.

How the texts are stored

You may have learned that the program internally converts Greek characters into Latin letters:

this aims at helping researchers who are unfamiliar with the Greek language. Also,

spaces, commas, periods and capitalized letters are completely ignored.

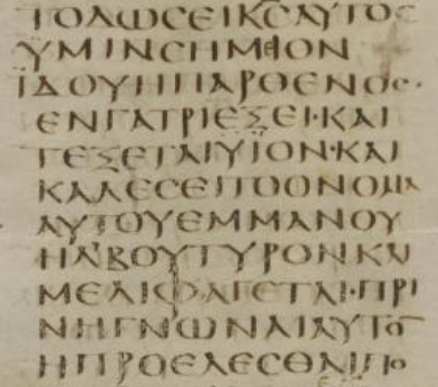

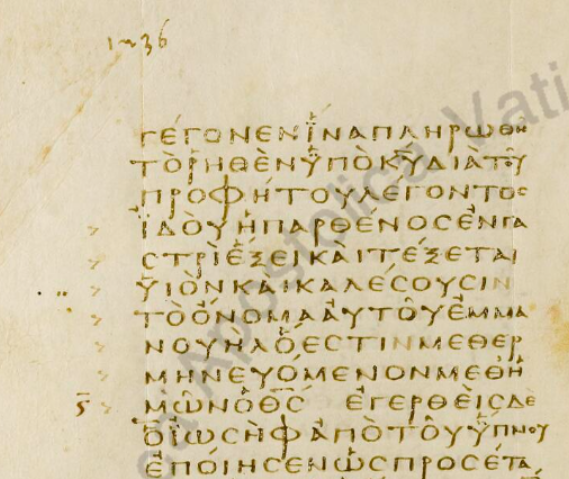

This is intentional: the manuscripts from the 4th century CE do not have any punctuations. Here are

two examples, taken from the freely available databases for the Codex

Vaticanus and the Codex Sinaiticus.

In fact, chapters and verses for the Bible were introduced in the 13rd century (by Stephen Langton)

and widely accepted just in the 16th century.

This first picture is a snapshot from Codex Sinaiticus, in the passage near Isaiah 7:14.

The second picture below is from Codex Vaticanus, in the passage near Matthew 1:23 (on page 1236,

if you want to search for it on your own).

Can you find the word Immanuel in both texts?

Acknowledgment. My friend László Gyöngyösi kindly helped me improve the first version

of this blog entry.

Entries on topic internal references in the Bible

- Web version of bibref (12 January 2022)

- Order in chaos (17 January 2022)

- Reproducibility and imperfection (20 January 2022)

- A student of Gamaliel's (23 January 2022)

- Non-literal matches in the Romans (26 January 2022)

- Literal matches: minimal uniquity and maximal extension (31 January 2022)

- Literal matches: the minunique and getrefs algorithms (1 February 2022)

- Non-literal matches: Jaccard distance (2 February 2022)

- Non-literal matches in the Romans: Part 2 (3 February 2022)

- A summary on the Romans (5 February 2022)

- The Psalms (6 February 2022)

- The Psalms: Part 2 (7 February 2022)

- A classification of structure diagrams (15 February 2022)

- Isaiah: Part 1 (19 February 2022)

- Isaiah: Part 2 (26 February 2022)

- Isaiah: Part 3 (2 March 2022)

- Isaiah: Part 4 (7 March 2022)

- Isaiah: Part 5 (15 March 2022)

- Isaiah: Part 6 (23 March 2022)

- Isaiah: Part 7 (30 March 2022)

- A summary (7 April 2022)

- On the Wuppertal Project, concerning Matthew (17 July 2022)

- Matthew, a summary (25 July 2022)

- Isaiah, a second summary (31 July 2022)

- Long false positives (23 August 2022)

- A general visualization (25 August 2022)

- Stephen's defense speech (19 September 2022)

- Statistical Restoration Greek New Testament (31 July 2023)

- Qt version of bibref (11 March 2024)

- Statements on Bible references (5 August 2024)

- Statements on Bible references: Part 2 (2 January 2025)

- Statements connecting LXX and StatResGNT (23 January 2025)

- Deuterocanonical books in the bibref project (5 February 2025)

- Update to LXX 3.0: Part 2 (7 February 2025)

- An allusion on Palm Sunday (29 March 2025)

- Module LXX can be upgraded from 3.0 to 3.2 just with little pain (14 August 2025)

- bibref: German language support (23 August 2025)

- Statement diagrams based on LXX 3.2 (24 December 2025)

|

Zoltán Kovács Linz School of Education Johannes Kepler University Altenberger Strasse 69 A-4040 Linz |